The Russian bathhouse—or banya—is something of a national institution. Babies were traditionally delivered in them, and poet Alexander Pushkin claimed they were “like Russia’s second mother.” The one in the basement of the Winter Palace in St. Petersburg was Catherine the Great’s favorite spot for her amorous trysts with Prince Grigory Potemkin. And Peter the Great was such a fan that he insisted on one being built on the banks of the Seine when he visited Paris in 1718.

The Moscow-based decorator Kirill Istomin is less keen on sweating it out. “They weren’t such a part of my upbringing, because I didn’t spend all my life in Russia,” he says. He moved to the United States as a teenager (his father was an architectural consultant at the World Bank) and began his career at the age of 18 in the offices of the hallowed New York interior design firm Parish-Hadley. He still very clearly recalls his first meeting with its legendary principal, Albert Hadley: “He looked at my work and said, ‘Wow! This is the most colorful portfolio I’ve seen in my life!’ ”

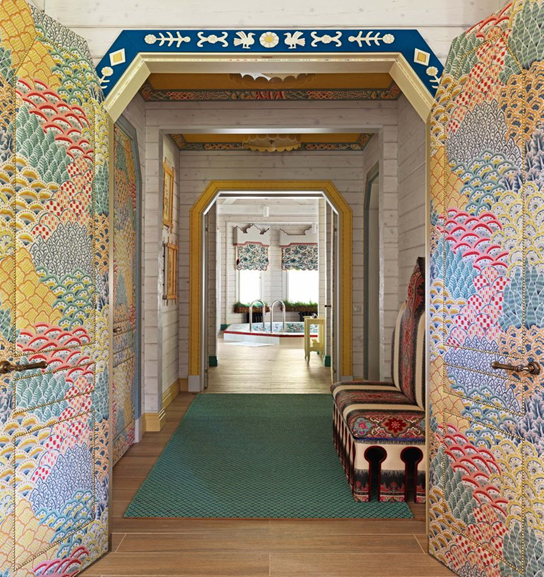

Many Russian country houses today still have banyas at the bottom of the garden, and this wooded property in a gated community to the west of Moscow is no exception. Its banya is just somewhat grander than most—rather than a simple sauna-like structure, this one also incorporates an entry hall, a kitchenette, and a lofty living room, where Istomin’s clients, a young couple with three children, can entertain. Istomin made few changes to the actual building. The wooden walls and ceilings were simply bleached, and new doors were installed with angular frames copied from 16th-century examples.

When it came to the decoration, however, Istomin most certainly went to town. His inspirations included the stage sets of Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, Yves Saint Laurent’s Normandy dacha, and Russian folk art. He shunned historical accuracy—his goal was to conjure up an idealized vision of his native land. “It’s like the dream of a beautiful, exotic Russia that never existed,” he says.

The focal point is an immense glazed-ceramic stove based on a 17th-century design. Equally extravagant is the sitting room’s chandelier—a painted-wood reproduction of a late-19th-century model he found in a book on the architect Nikolai Pozdeev, best known for the Igumnov House in Moscow, which now serves as the official residence of the French ambassador to Russia. Elsewhere are a dazzling array of fabrics, with pattern upon pattern and a plethora of window treatments.

There are pelmets with forms mimicking window casings of 16th-century terem palaces, and a wing chair upholstered with a patchwork quilt acquired on a weekend trip to one of Russia’s oldest towns, Suzdal. Wherever possible, Istomin called upon local artisans and integrated traditional crafts. Chairs are embroidered with belts from national costumes; cushions are made from vintage shawls.

Striking exceptions are the four dining chairs sculpted with different animals, which look as if they’ve stepped straight out of a Russian fairy tale. In fact, they were acquired from Anthropologie and then cleverly repainted and reupholstered. “If you saw the originals, you’d never believe they were the same,” Istomin says with glee. Inexpensive, inventive, and wonderfully whimsical, they consummately capture the spirit of the project as a whole. As Istomin insists: “This is not a serious house. It’s a playful fantasy world.”

Your Message